Artificial heart research at the Cleveland Clinic

Once more, luck was with me. I was taking a female friend, not a girlfriend, to a folk dance. She lived with three other young women in a large house. It was the culture back then for the guys to sit in the living room and wait. We were supposed to wait and wait.

We guys chatted about stuff, and one guy asked me what I did for work. At that time, I was the antenna tuner/inspector for Antenna Specialist in East Cleveland on Euclid Ave, only two blocks from where I lived. He politely grilled me on my background in electronics. He then suggested that I apply for a job in the lab next to where he worked. I had never heard of this hospital/clinic, but he set it up and gave me directions.

I applied, and the interview was during surgery to replace the natural heart with an artificial heart in a dog. I learned later that the purpose was to see if I could stomach the operation without throwing up. I came from a farm background and had always cleaned the rabbits and squirrels that I shot, so a dog cut open was nothing to me.

The big boss asked me into his office after I passed the first “test.” He wondered about Ham Radio and wondered if it was taught in our public schools. I answered no; it was just my hobby. That was it, as he wanted people who operated from passion, not from school education.

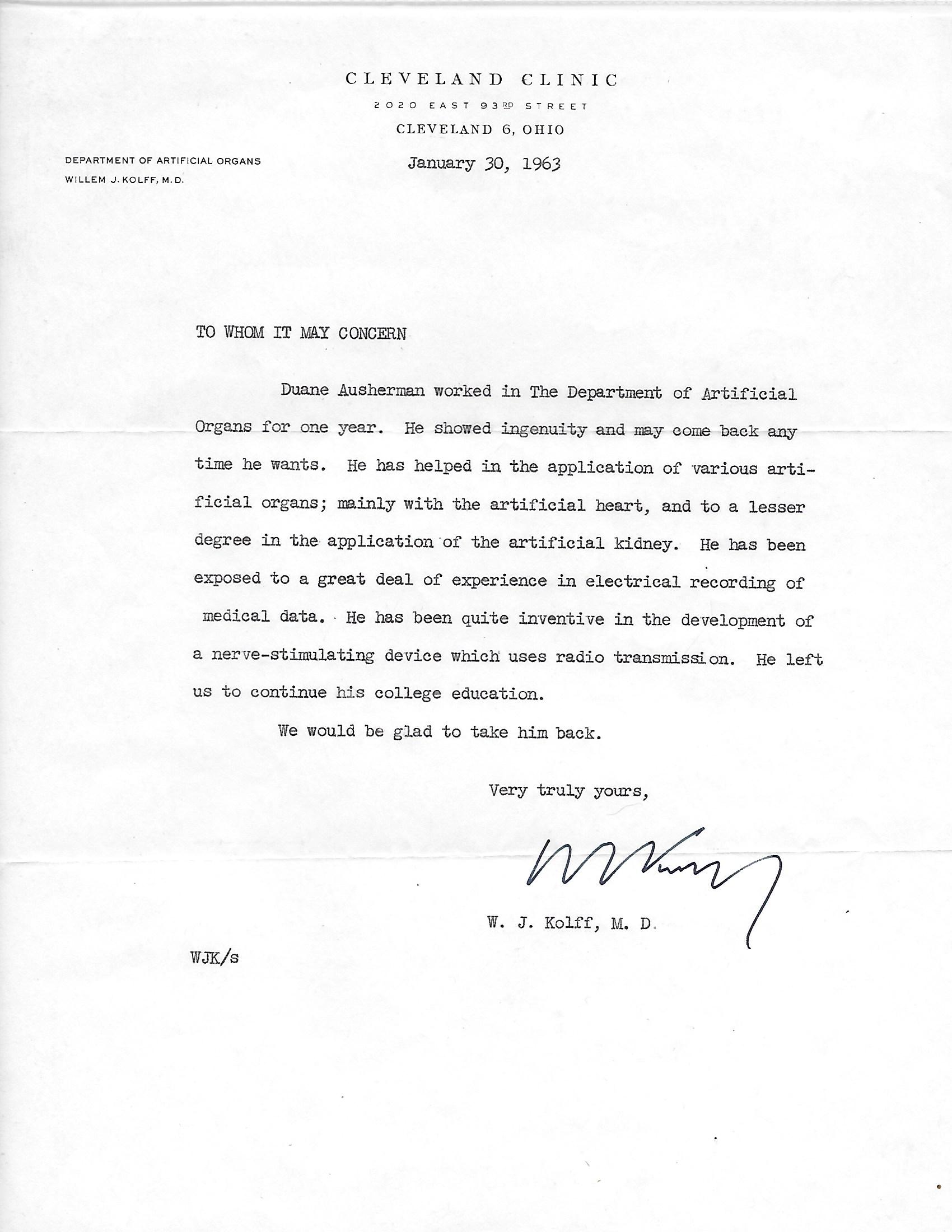

I stayed for a year and left to go back to college. Working there had been an eye-opener, and I wanted more education. However, college wasn’t for me, so I returned a year later and resumed my job with the artificial heart. Dr. Kolff was true to his word, and he was happy to take me back.

I worked at the Cleveland Clinic in the Department of Artificial Organs from 1962 to 1964, and it included the artificial kidney, heart, heart-lung machine, and more. The Dept. head was Dr. Willem Kolff from Holland. He single-handedly invented and developed the artificial kidney. The result is a world full of Dialysis Centers.

My job as an electronics technician was primarily in electronics and secondarily as a surgical assistant in heart replacement. We tried many types of mechanical devices to pump blood, but the most successful was the Akutsu sack-type pump. It was invented by Dr. (Ted) Tetsuzo Akutsu in our lab in 1961.

The “heart” shown above is only one of 4 chambers of the heart. It is the left ventricle. The connections to the natural body are on the right side. The lower one (larger) is the pulmonary vein, and the upper (smaller) is for the aorta. The hose connection on the aorta is for monitoring the pumping of blood pressure. The blood pressure waveform does not resemble the typical aortic wave because here, it is measured in the ventricle, not on the other side of the valve. The ventricle is powered by air pressure from an external source, and its connection is in the center of the photo. Surrounding that connection is a round ridge. This ridge is covering a coil of wire. Another coil of wire is on the other side of the ventricle. The coil of wire is part of the electrical measurement to instruct the computer to pump properly. Wires led out of the body to the equipment. They were always breaking at the heart due to the flexing. I replaced the coils with a radio transmitter. The problem was solved, thanks to amateur radio.

The “pump” is two sacks, one inside of the other. Air is pumped in between the two, and since the outer one can’t expand much, the inner one collapses, forcing the blood out. A ball valve would be mounted in each of the two connections. The place where sutures tied the valve in place can be seen as ridges in the last 1/4″ of the connection. The white spot in the center is a repair job made of RTV Silicone. The “heart” was made from Dacron fabric embedded into Silicone by Dow Corning. During my time, we made them by hand. One of my jobs was making the woods metal molds upon which the Silicone fabric was laid.

We replaced a natural heart with one, sometimes two, animals per week. This heart was used in 1963 to replace the heart of a dog. Dogs survived only about 24 hours. The doctors decided that dogs were unsuitable and abandoned as test subjects. Since pigs were very close to humans, we tried to use pigs. That failed due to the difficulty with general anesthesia. The pigs would die before the anesthesia would take effect. Then we used calves and got a longer survival time.

Recently a national advertising campaign by Pfizer for the drug Lipitor shows Dr. Jarvik as the inventor of the artificial heart. The ad implies that Dr. Jarvik is the sole inventor of the concept. It is not true at all. He would have to stand in a long line for that one. Dr. Kolff was the first to implant a completely artificial heart in an animal. Many other laboratories were working on a variety of blood-pumping devices. When Dr. Kolff retired, the lab was taken over by Dr. Jarvik. He carried on with the research, and it progressed. He developed a mass-production method of making hearts. He also got government approval for testing on humans. That was long after my tenure at the Cleveland Clinic. Pfizer has some wonderful products; they do not need to “cheapen” their image by making misleading claims.

Artificial heart research was one of the most interesting jobs I have had. My boss, Dr. Kolff, was one of my best bosses. To get a chance to work with such great people, such as Dr. Akutsu, was beyond my highest hopes.

My interest in medicine never left, and later I became an EMT in Fort Bidwell, Ca. my country home from 75-93.

I loved this job and may return to add more to it.

The artificial Placenta

Babies born prematurely were not likely to survive if too small. Their heart and lung functions were not fully developed, or so it was thought.

Dr. Kolff wanted to build a small heart pump and lung for these babies. The pump would be a small roller pump similar to that of a heart-lung machine. The lung would be much smaller than the normal membrane-type oxygen transfer. As I remember, it was two semi-permeable membranes in a sandwich. Pure oxygen flowed on both sides of the membrane. The membrane was about 8″ wide by 12″ high. This was more than enough to oxygenate the small amount of blood flow.

These small babies had a circulating blood volume, and the volume of blood in the machine was much larger. It was thought that the blood volume should be controlled to within a few ccs to avoid shock and likely death.

While I worked on the general construction of this machine, it was my sole responsibility to find a way to control the blood volume to a very high degree. I found that a very simple electrical circuit using one transistor as the switch would do the job quite well.

Dr. Kolff was so impressed that he politely “suggested” that I write it up. I was embarrassed as this simple circuit might appear in chapter one of a kindergarten-level electronics book. I assumed that it would never get published. It not only got published, but my name was on it. One of the great things about Dr. Kolff was that he was very generous about giving credit. I guess that it was a big part of the reason why all of us employees loved him.

What we called an artificial Placenta would now be a neonatal device. I left about the time that this machine was ready for testing on an animal.

Since dialysis is really quite a simple procedure, Dr. Kolff came up with the idea of converting wringer-type clothes-washing machines into the artificial kidney. These could be placed at the home of a kidney patient of a family trained to operate it.

We purchased 5 machines to convert to an artificial kidney. My only contribution was to add the controls for the blood pump. The largest challenge was finding families who were willing and capable of using the machine. Since this was a clinical device, I didn’t follow the project to learn about its success. Had it failed, I would have heard about it.

Updated 30 March 2023